The Hearth

The ancients associated this part of the body, including the heart, with the hearth, and regarded it as the seat of memory. The hearth was the center of the home as well as the place of contact with ancestors. It was the place where the family gathered and traded experiences of the day, recalling in the process the words and deeds of the past. Without memory there is no family, even if the people living together are all related, as we know now that the hearth has been replaced by the television or computer as the central focus of the house, especially if meals are taken individually in the living room.

In the old days, the hearth gave heat and light to the home and was also where food was cooked. Nowadays some are fortunate enough to own a house with a fireplace, but they usually have a stove as well, so that the functions of the ancient hearth have become divided, and it is difficult to decide where to place the hearth shrine.

I have no fireplace where I live now, so my hearth shrine is near my stove. My stove is electric, but I keep a large candle in the shrine and light that, together with stick incense, when I want to awaken the hearth guardian. Additionally, I keep there somewhat larger versions of the offering dishes described above for the threshold shrine.

The hearth guardian is both a goddess and the hearth fire itself. In ancient Latium she was called Vesta. She accepts offerings for herself and also passes on some of them to the ancestors, godlings and blessed immortals. Because I cannot maintain a perpetual flame, I have a picture of her in my shrine, and close to her picture is a statuette of my family lar. The lar familiaris is an ithyphallic youth pouring wine from a wineskin into a chalice. He symbolizes the vigor and luck of my family line, and as such forms a link back to the ancestors, and onward to posterity. If I want to honor and pray to another deity, I can conveniently place his or her statue in the shrine for the occasion. This saves on shrines. At the shrine or close by are photos of my parents and maternal grandmother. These are the ancestors who were my caregivers when I was small, and with whom I still share a bond of love. The Romans and other ancient peoples represented their ancestors by small clay figurines on the altar, as seen in some recent films.

When my offerings are laid out, I light the candle saying "Honor to fire, honor to Vesta, honor to the hearth." Then I light the incense. Then I pray: "Holy Lady, please accept these offerings of salted grain and pure water, light and scent for thine own dear self, and pass on some to the lares and penates, the di manes, daimones and blessed gods, thanking them for their good regard for me and my family, and asking for a continuance of their favor." To this basic prayer I add anything special for other deities. While the fire is lit in the shrine, I call on my ancestors and talk to them. I let them know how things are going in the family with me, my sons and grandson, our concerns, blessings, problems and plans, just as I would if they were still in the flesh. If any of them has appeared recently in a dream, I thank him or her for the visit.

At the close of the rite, I bid farewell to ancestors and deities and extinguish the candle, letting the incense burn down. I say the opening prayer in reverse order, ending with "Honor to the hearth, honor to Vesta, honor to fire." In Roman houses the hearth shrine was decorated with fresh flowers and offerings made at least three times in the lunar month: on the Calends, that is, the day after the dark moon; on the Nones, the ninth day before the full moon; and on the Ides or full moon itself. In Caesar‟s solar calendar the Ides was regularized as the fifteenth of each month, which would place the Nones on the seventh.

The Inner Hearth

When we practice "standing in the doorway,‟ we naturally do not do so all the time, and this provides us with a contrast between the two modes of experience, so that we begin noticing things that were formerly invisible to us because they were constant. Some of these things are external to our minds, such as shadows and clouds, and some are internal. One of the internal things is the synopsis or background summary we take to experience, the mental account we refer to offhand when answering the common question "How is it going?" The synopsis is more readily observed in dreams, because it is different for each dream-story or sequence, whereas in waking life it is ongoing and only changes gradually except in moments of crisis.

When we enter a dream-story we generally enter in the middle of it, provided with a ready-made background that tells us where we are and what we are supposed to be doing. We are provided with dream-memories, sometimes selected from previous dreams (as in recurring dreams), and unless we become aware we are dreaming, we do not question it or the actions of other dream-figures.

Similarly, in waking life we are generally absorbed by the problems and affairs of the moment, as supplied by an ongoing mental summary or synopsis. From this we derive our sense of who we are in the present and what we need to do. The synopsis is based on a selection of memories, and these change gradually unless we are in the throes of a crisis, in which case we need to revise our orientation, sometimes on the basis of earlier memories, in order to cope with the situation. At times our synopsis can become so obsessive that we throw it over in a breakdown and temporarily become disoriented.

Standing in the doorway provides a milder sort of disorientation, as the contrast between it and our usual awareness brings the operation of the synopsis to the forefront of attention. Then, as in the onset of lucid dreaming (when we suddenly realize we are dreaming), we become free to question who we are supposed to be and what we are supposed to be doing in the present moment. The process of interpreting present experience in terms of our usual selection of memories is suspended, and earlier memories are able to surface, bringing with them earlier feelings of ourselves and of life, derived from past synopses. This is a familiar experience when we go on a trip, especially if we visit old neighborhoods we haven't seen in many years, and perhaps explains why we like to take such trips after surmounting a difficult crisis.

Vesta's power to call up the ancestors from old memories works in a similar way, and when our focus of awareness has moved to the chest or solar plexus, continual standing in the doorway can help her to perform the same feat for us at our inner hearth, especially if we augment our headless attention with another pre-verbal mode of awareness involving sound.

The first stage is to listen to all the sounds around us, without dividing them into „background‟ and "foreground‟. This comes about naturally

once our visual attention rests on the limits of the visual field instead of tracking on this or that object. It is easy for the attention to waver, however, so the focus on sounds must be augmented by mentally copying sounds just heard.

Small children learn to speak by mentally copying sounds, and there is reason to believe that animals do something similar. Mentally copying sounds and associating them with specific situations would seem to have been a major part of humanity's pre-verbal thought processes. Once we learn to speak, and to speak to ourselves, mental mimicry of sounds is relegated to a minor role and generally limited to copying sounds for which we have words. When we begin "thinking with the chest,‟ like Ochwiay Biano, our minds become quieter and we become aware of feelings and images for which we have no words, not because they are ineffable, but simply because no words have yet been assigned to those experiences. Consider smells, for instance. We have many words for colors and quite a few for sounds, but our olfactory vocabulary is very limited. If a dog could be taught to speak, he would find himself at a loss to describe the many odors in his daily experience. If he invented words for the many different odors, we would find it hard to understand him, lacking referents because we are purblind in our noses.

In the same way, this particular sound I have just heard has no precise word describing it. We can say, „that is the sound of a car engine,‟ as we say „that is a tree,‟ and ignore sensory detail in either case. Our everyday minds can deal with such thumbnail descriptions without having to disturb the selection of memories forming a background to our moment-to-moment synopsis. But if we mentally repeat the precise sound of that car that just went by, our memory background is rendered more porous, as it would become in a crisis, so that feelings and images from past memories are able to emerge.

I tried mentally echoing sounds just heard as an experiment in 1972, while walking along a busy street in Encanto, California. I was also keeping my sunglass frames in view, an earlier version of „standing in the doorway‟. I did this for an hour or more, and recorded the results in a journal:

"The result of this double exercise was three full days, not counting sleep, in silent awareness of total sensation…At one point the feeling of lightness became like a breeze flowing through my body from back to front. Everything seemed to take on a bluish tinge…By the third day, the breeze had risen to a light wind and was blowing through my memories. My personal history, the sense of who I am, was being shuffled like a deck of cards…By the end of the third day the wind set me down somewhere else in myself; that is, my store of familiar memories was completely revised and my feeling of myself permanently changed from that point on."

After this experience, my dead grandmother began visiting me regularly in my dreams. I noticed that in many of these dreams I appeared to be younger, and to feel as I did when she was still alive, but my understanding was linked to the present. It was common to realize at the time that I was dreaming, if not at first then as the dream progressed, for I would remember that she had died. These earlier feelings of myself, and of my grandmother when she was alive, enhanced a feeling of harmony with her and allowed us to converse in close intimacy. However, as I had no unresolved issues with her, there was nothing specific to work through. I usually asked her how she was, and she said fine, but she felt tired a lot, and this probably came from memories of her as she was towards the end of her life.

My practices of the threshold and hearth continued over the next several years, and long after my father died I did have some serious issues to work through with him. This took about three years to get through, during which time I was periodically out of work (I was doing contract programming and moving around a lot). In both dream and waking I agreed with my father to resolve certain problems for good with him in exchange for obtaining help in finding employment. On each of three occasions, I received job offers within twenty-four hours of these conversations. Skeptics may make of this what they will; but taking the view that I was in contact with the spirits of my ancestors, it makes sense that they would find it easier to relate to me after I had recovered earlier feelings of myself and of them which I had when they were still alive.

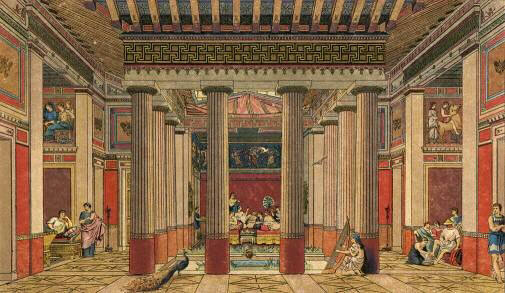

Ancient Greek Interior

Inside an ancient Greek house

Friday, November 11, 2011

Thursday, November 10, 2011

The Sacred Household, Part 1: The Threshold by Ian Elliott

The Sacred Household: Rites and Mysteries

The Threshold

The sacred household in ancient and more recent indigenous cultures bears certain analogies to the human body. The front door is similar to the eyes, the hearth to the heart or solar plexus, and the central supporting pillar to the spine. Shrines or altars at these locations were guarded by spirits who were linked with internal spirits in each family resident, and the proper worship of the household guardians involved being on familiar terms with their inner analogues and tending their inner shrines.

This study of the sacred household uses the names of Roman household spirits, but it is based more broadly on a number of other cultures. We no longer live in Roman houses, so some latitude must be taken in locating household shrines; and we are not all of Roman descent, so some attention must be paid to the forms of piety practiced by our ancestors from other lands.

It is not enough to study household rites and set up modern versions of ancient shrines. Our early conditioning separates us from some pre-verbal modes of awareness, by teaching us to ignore certain readily available perceptions; these must be recovered if we are to properly install our internal shrines and so link them with those of the household. I have called practices that open up these perceptions „mysteries,‟ because having been forgotten they have become secret things.

The Roman god of the threshold was Janus, who has two faces, one looking outside and the other inside the home, as well as forward and backward in time. To enter a house, as H.J. Rose pointed out in Religion in Greece and Rome, 1 Rose, p. 179 is to begin something, and so household piety. always began by honoring Janus at the threshold. His annual festival was on January 9th, 2 and offerings at his shrine were made on the Calends (the day after the dark moon of the lunar calendar), as well at the beginning of any endeavor, such as a journey; also on one's birthday. 3 The Romans, even after they came under Greek influence, were by preference an aniconic people; that is, they preferred worship without images. Perhaps this was because they focused on the link between the inner and outer shrines and found external images a distraction. I keep my own threshold shrine simple, hanging a god-face about a foot and a half above a small offering shelf, the shelf set next to the front door a little above eye-level. On the shelf is a candle, a stick incense holder, toy-sized dishes for water and salted grain.

Upon crossing the threshold one always steps over it, never on it, and one should touch the doorpost as an acknowledgement of the threshold guardian and to receive his numen. We can tentatively define numen as liberating and empowering energy that is unknown or at least unfamiliar. My prayer when offering to Janus is the same as the one I used when setting up his shrine:

Honor and thanks to you, O Janus,

for guarding the threshold of my home.

May only harmonious beings enter here,

and may the discordant depart!

Please accept these offerings of salted grain, water, light and scent,

Open this week [month, journey, etc.] for me on blessings,

and teach me to look out and in at once as you do,

so I may guard the threshold of my inner home; for I, too, am a threshold guardian.

The god-face for Janus looks straight in, as I prefer to imagine his head imbedded in the wall, with his outer face guarding the outside of my doorway.

The Inner Threshold

This ability to look out and in at the same time holds the clue to Janus' mysteries, to the pre-verbal mode of perception that will give us the ability to look in the same manner, outward and inward simultaneously. To do this we must „stand in the doorway,‟ and the best description of this was provided by Douglas Harding in his important little book On Having No Head. Harding was hiking in the Himalayas and one morning he suddenly saw the world differently:

"…I stopped thinking…Past and future dropped away. There existed only the Now, that present moment and all that was given in it. To look was enough. And what I found was khaki trouserlegs terminating downwards in a pair of brown shoes, khaki sleeves terminating sideways in a pair of pink hands, and a khaki shirtfront terminating upwards in – absolutely nothing whatever! Certainly not in a head." 4 4 Harding, p. 2. This nothing, however, was filled with everything: mountains, sky, valleys below, extending to the horizon. Harding felt light and liberated. He had ceased to ignore the sensations of his own headlessness, ending a habit acquired in infancy when told that „the baby in the mirror‟ was merely his own reflection. In addition to his headlessness, he was now attending to the limits of his perceptual field. Consequently, he wasn‟t tracking on this or that object, as we spend so much of our time doing, using our eyes as searchlights for our impulses and desires. Instead, he was looking at his whole visual field at once, and the lightness he felt resulted from dropping the burden of his eyes from incessant tracking, and of his mind from incessant thinking.

Indigenous peoples are aware of the difference between these two ways of looking at the world. When the psychologist C. G. Jung visited an Indian pueblo in the American Southwest years ago, he had a conversation with the local chief, Ochwiay Biano (his name means Mountain Lake).

"The white man‟s eyes are always restless," the chief told Jung. "He is always looking for something. We think he is mad."

Jung asked him why they thought that.

"He says that he thinks with his head."

"Why of course," answered Jung. "What do you think with?"

"We think here," he answered, indicating his chest. 5

There are two potential errors in assessing what Ochwiay Biano said. One is to take his words sentimentally, as if he were merely speaking of „heartfelt thinking.‟ The other error would be to dismiss his words as expressions of a primitive, pre-scientific physiology. The Pueblo chief would not have been troubled to learn that Western science has determined through experiments that we think with our brains. This would have seemed to him irrelevant to what he was talking about, namely the sensation of where the thinker seems to be located in the body. We feel we are located in our heads because of certain muscular tensions around the eyes from tracking, and in our foreheads from „knitting our brows,‟ and performing other social cues indicative of taking thought. But these external muscular contractions, though spatially closer to the brain, are nevertheless external to it and involve muscles on the outside of the head. The feeling we get from them of being „in our heads,‟ therefore, is no more scientific than the feeling the Pueblo chief evidently got of being in his chest.

When we look at our headlessness, our chests come into view as the closest part of the body that is completely visible; and when mental talk quiets down as a result of tracking being replaced by restful awareness of the whole available visual field, words are employed only as and when necessary for external communication. The rest of the time one simply looks, listens and understands, and this quieter form of awareness allows feelings to come to the fore since they are no longer drowned out by incessant mental chatter. For these reasons, Ochwiay Biano felt that he thought in his chest, or solar plexus.

The Threshold

The sacred household in ancient and more recent indigenous cultures bears certain analogies to the human body. The front door is similar to the eyes, the hearth to the heart or solar plexus, and the central supporting pillar to the spine. Shrines or altars at these locations were guarded by spirits who were linked with internal spirits in each family resident, and the proper worship of the household guardians involved being on familiar terms with their inner analogues and tending their inner shrines.

This study of the sacred household uses the names of Roman household spirits, but it is based more broadly on a number of other cultures. We no longer live in Roman houses, so some latitude must be taken in locating household shrines; and we are not all of Roman descent, so some attention must be paid to the forms of piety practiced by our ancestors from other lands.

It is not enough to study household rites and set up modern versions of ancient shrines. Our early conditioning separates us from some pre-verbal modes of awareness, by teaching us to ignore certain readily available perceptions; these must be recovered if we are to properly install our internal shrines and so link them with those of the household. I have called practices that open up these perceptions „mysteries,‟ because having been forgotten they have become secret things.

The Roman god of the threshold was Janus, who has two faces, one looking outside and the other inside the home, as well as forward and backward in time. To enter a house, as H.J. Rose pointed out in Religion in Greece and Rome, 1 Rose, p. 179 is to begin something, and so household piety. always began by honoring Janus at the threshold. His annual festival was on January 9th, 2 and offerings at his shrine were made on the Calends (the day after the dark moon of the lunar calendar), as well at the beginning of any endeavor, such as a journey; also on one's birthday. 3 The Romans, even after they came under Greek influence, were by preference an aniconic people; that is, they preferred worship without images. Perhaps this was because they focused on the link between the inner and outer shrines and found external images a distraction. I keep my own threshold shrine simple, hanging a god-face about a foot and a half above a small offering shelf, the shelf set next to the front door a little above eye-level. On the shelf is a candle, a stick incense holder, toy-sized dishes for water and salted grain.

Upon crossing the threshold one always steps over it, never on it, and one should touch the doorpost as an acknowledgement of the threshold guardian and to receive his numen. We can tentatively define numen as liberating and empowering energy that is unknown or at least unfamiliar. My prayer when offering to Janus is the same as the one I used when setting up his shrine:

Honor and thanks to you, O Janus,

for guarding the threshold of my home.

May only harmonious beings enter here,

and may the discordant depart!

Please accept these offerings of salted grain, water, light and scent,

Open this week [month, journey, etc.] for me on blessings,

and teach me to look out and in at once as you do,

so I may guard the threshold of my inner home; for I, too, am a threshold guardian.

The god-face for Janus looks straight in, as I prefer to imagine his head imbedded in the wall, with his outer face guarding the outside of my doorway.

The Inner Threshold

This ability to look out and in at the same time holds the clue to Janus' mysteries, to the pre-verbal mode of perception that will give us the ability to look in the same manner, outward and inward simultaneously. To do this we must „stand in the doorway,‟ and the best description of this was provided by Douglas Harding in his important little book On Having No Head. Harding was hiking in the Himalayas and one morning he suddenly saw the world differently:

"…I stopped thinking…Past and future dropped away. There existed only the Now, that present moment and all that was given in it. To look was enough. And what I found was khaki trouserlegs terminating downwards in a pair of brown shoes, khaki sleeves terminating sideways in a pair of pink hands, and a khaki shirtfront terminating upwards in – absolutely nothing whatever! Certainly not in a head." 4 4 Harding, p. 2. This nothing, however, was filled with everything: mountains, sky, valleys below, extending to the horizon. Harding felt light and liberated. He had ceased to ignore the sensations of his own headlessness, ending a habit acquired in infancy when told that „the baby in the mirror‟ was merely his own reflection. In addition to his headlessness, he was now attending to the limits of his perceptual field. Consequently, he wasn‟t tracking on this or that object, as we spend so much of our time doing, using our eyes as searchlights for our impulses and desires. Instead, he was looking at his whole visual field at once, and the lightness he felt resulted from dropping the burden of his eyes from incessant tracking, and of his mind from incessant thinking.

Indigenous peoples are aware of the difference between these two ways of looking at the world. When the psychologist C. G. Jung visited an Indian pueblo in the American Southwest years ago, he had a conversation with the local chief, Ochwiay Biano (his name means Mountain Lake).

"The white man‟s eyes are always restless," the chief told Jung. "He is always looking for something. We think he is mad."

Jung asked him why they thought that.

"He says that he thinks with his head."

"Why of course," answered Jung. "What do you think with?"

"We think here," he answered, indicating his chest. 5

There are two potential errors in assessing what Ochwiay Biano said. One is to take his words sentimentally, as if he were merely speaking of „heartfelt thinking.‟ The other error would be to dismiss his words as expressions of a primitive, pre-scientific physiology. The Pueblo chief would not have been troubled to learn that Western science has determined through experiments that we think with our brains. This would have seemed to him irrelevant to what he was talking about, namely the sensation of where the thinker seems to be located in the body. We feel we are located in our heads because of certain muscular tensions around the eyes from tracking, and in our foreheads from „knitting our brows,‟ and performing other social cues indicative of taking thought. But these external muscular contractions, though spatially closer to the brain, are nevertheless external to it and involve muscles on the outside of the head. The feeling we get from them of being „in our heads,‟ therefore, is no more scientific than the feeling the Pueblo chief evidently got of being in his chest.

When we look at our headlessness, our chests come into view as the closest part of the body that is completely visible; and when mental talk quiets down as a result of tracking being replaced by restful awareness of the whole available visual field, words are employed only as and when necessary for external communication. The rest of the time one simply looks, listens and understands, and this quieter form of awareness allows feelings to come to the fore since they are no longer drowned out by incessant mental chatter. For these reasons, Ochwiay Biano felt that he thought in his chest, or solar plexus.

Monday, October 24, 2011

Moving Back to Yahoo

I have decided to move the contents of this blog to a Yahoo Group called Household Paganism, if that is available. I cannot deal with the frustration of struggling with Google Blogger, which has no real personal technical support and is extremely convoluted to use, a sure sign (to an old mainframer like me) of poor design. Life is too short and has too many real problems to deal with. After I set up the Household Paganism group on Yahoo, I will send out invitations to join to the current blog membership.

Bright Blessings,

Ian

Bright Blessings,

Ian

Thursday, October 20, 2011

Witchcraft subject moved to a different blog

I have decided that Household Paganism is a sufficient focus for one blog. I have started a new blog for the sort of witchcraft I propose to teach, called Hedge Witchcraft. This will be witchcraft mainly for solitaries, or for two or three witches (not enough for a coven) who are in contact with each other physically or on the internet. I will add a link to the new blog here once it is sufficiently constructed.

Right now I am hunting for the best article on Roman Domestic Religion I can find for this blog. The address for this blog retains 'and witchcraft' so present members can still find it.

Ian

Right now I am hunting for the best article on Roman Domestic Religion I can find for this blog. The address for this blog retains 'and witchcraft' so present members can still find it.

Ian

Saturday, October 1, 2011

Greek Domestic Religion

Greek Domestic Religion

Ian Elliott August 17th, 2011

Introduction

Those of us interested not only in studying but emulating ancient religion naturally take an interest in the domestic religion of ancient peoples, for unless we live among surviving or revived pagan communities, we are reduced to celebrating ancient piety in solitude, or with our families. Judging by recent scholarship, there has been a steady increase of interest in sacra privata, the sacred privacies, and though evidence for such is scanty compared to that available for ancient civic religion, more is being revealed by the efforts of archæologists, epigraphists and scholars as time goes on.

The information available on domestic religion in ancient Greece and Rome, though fragmentary, is far too voluminous for a single lesson, and I have limited the topic to those things that apply to the home and its immediate environs, and to those activities most adaptable to modern use. Thus, while both the Greek guardian of the family storehouse, Zeus Ktesios, and the genii loci or genius and juno of the Roman household were depicted as snakes, and there is ample evidence of household snakes (harmless grass snakes where the species is known) from ancient Crete to medieval Lithuania and even later, most of us are unlikely to take up this age-old custom of keeping one in the house or under the front porch. So passing mention will be made of the practice only to illustrate certain features of the guardian spirits later conceived, at least in Rome and partly, in human form.

Allowances must also be made for the differences in ancient and modern architecture, especially as regards the hearth, when seeking to import Greek or Roman domestic religion into today’s homes. Those of us who are fortunate to have a fireplace can set up a shrine there to Hestia or Vesta and the ancestors and guardian spirits, but in most modern homes fireplaces are ornamental even when fully functional, and do not replace the stove or central heating. Currently I have no fireplace and so maintain a small shrine in the kitchen, getting it as close to the stove (and as far from the smoke alarm) as possible.

Finally, I have limited this study to Greek and Roman households, even though the material from other cultures (for instance, the Ainu of Sakhalin before WWII) is richer, in some cases assigning sacred meanings to all features or areas of a home. Those who have ancestral or far memory links to other cultures are invited to extend this study to those peoples.

Greek Domestic Religion

The material presented in this section is derived from a recent Master’s thesis presented to the University of Cincinnati by the scholar Katherine Swinford. Her primary interest was in the implements employed in Greek household religion, but her introductory material on the religion itself is well presented and documented. [1]

Household Gods

The Greeks differed from the Romans in installing the major deities of Olympus in household worship, giving them domestic epithets indicating their functions there, whereas the Romans tended to identify their domestic deities by function alone. For this reason, H. J. Rose preferred to characterize Roman (and Italic) religion as a polydaemonism (concerned with little, or demi-gods) rather than a polytheism, at least at the domestic level.

In Greece, the gods whose household cult is mentioned prominently in ancient sources include Hestia, Zeus, Hermes, Hekate, and Apollo Agyieus (Apollo of the Streets).

Hestia is often invoked both first and last among the gods, in private as well as public rituals. If an animal was slaughtered and a sacrifice was performed in the house, the first pieces of the sacrificial meal were offered to her, just as at all meals a few pieces were laid on the hearth. This is the reason why it seems to have been customary to offer the first pieces of all sacrifices, even public ones, to Hestia. The position of Hestia is also reflected in semiphilosophical speculations, in which it is said that Hestia is enthroned in the middle of the universe, just as the hearth is the center of the house.

Hestia is the Greek goddess of the hearth and is the metonymic symbol for an entire household. The typically Greek explanation for this is that she invented living in houses. For this reason, a house was regarded primarily as a hearth, just as the community of houses was symbolized by the public hearth, in Athens located in the Prytaneion.

In the middle of the great living room of the Greek house, the megaron, was a fixed hearth. The hearth served not only as the locus for domestic activities such as cooking and heating, but also as the sacred center of the household, or oikos. Sacrifices took place there, and oaths sworn upon the hearth or to Hestia were powerful. The newborn babe was received into the family by being carried around the hearth, a ceremony which was called amphidromia and took place on the fifth or tenth day after birth.

As the guardian of the hearth, Hestia served as the protector of the household and its occupants. The hearth, as an altar of the goddess, functioned as a refuge for suppliants, and those who sought refuge at the hearth were protected, just as those who sought haven at altars within temples were inviolable.

The Greeks before a meal offered a few bits of food on the hearth and after it poured out a few drops of unmixed wine on the floor. The libation was said to be made to Agathos Daimon, the Good Daemon, the guardian of the house, who appears in snake form. It is not stated to whom the food offering was made, but if someone is to be mentioned it must be Hestia, the goddess of the hearth.

To overthrow the house, to demolish the altar within it, incurred a punishment which struck at the same time at the living generation and at all the line of dead ancestors and of descendants yet to be born. Thus, the hearth, as an altar of Hestia, represented and preserved households past, present and future.

Zeus Ktesios, Herkeios, Kataibaites

Zeus Ktesios, or Zeus of the property, guarded and increased the provisions and wealth of the Greek house. The ancients used to install Zeus Ktesios in their storerooms. He was kept in a kadiskos, a small, two-handled, unadorned earthenware container. The handles were wreathed with white wool and a saffron thread, and ambrosia, that is, water and olive oil and a variety of fruit, was poured in. The depiction of Zeus Ktesios as a snake led Nillson to speculate that the physical guardian of the stores was a snake used to frighten away thieves, and the contents of the kadiskos were a sacred meal provided to it regularly. We’ll get back to snakes when we discuss the Romans.

Zeus also appeared in two other guises in or around the Greek house. The Greek word for fence is herkos, and herkeios is an epithet of Zeus. According to Homer, the altar of Zeus Herkeios generally stood in the courtyard before the house, where sacrifices and libations were offered to him. By the classical era, houses in towns were built wall to wall, and the shrine of Zeus Herkeios was usually found in the megaron, or large living room common to Greek homes. As Zeus Kataibates (he who descends), Zeus protected houses against strokes of lightning, and his altar was found before the house or within, next to that of Zeus Herkeios.

Doorway Gods

While Hestia and Zeus were venerated within the house, a few gods, such as Hermes, Apollo Agyieus, “Apollo of the streets” and Hekate, received their due directly outside the Greek home. Literature describes the shrines or altars to these gods, who were guardians of the pathways and of traveling, as standing before the doorways of private dwellings. These shrines functioned as protection against illness, enemies and other types of evil.

Doorway gods were significant to the ancient Greeks. Klearchos of Methydrion, a pious man, took care to garland and clean his Hermes and Hekate each month. This indicates that individuals may have had more than one doorway shrine which may have been dedicated to more than one god.

The herm, the embodiment of the god Hermes, was a square shaft topped with a head and was always ithyphallic. Herms were often used as boundary markers and stood outside of public sanctuaries, between the city and the country, as well as before the doors of private dwellings. An Attic red-figure loutrophoros depicts a procession coming home from the fountainhouse. Standing before the doorway of the house is an altar and a bearded herm. The altar may have been an altar to Hermes, or perhaps it functioned to represent one of the two other doorway gods. In Wasps, Philokleon mentions the altars of Hekate, set up before the doors of every citizen (Aristophanes, V. 804). The scholia to Aristophanes note that the altars erected to Apollo Agyieus were square in shape. A shallow recess near the street-side door, a feature common to many Classical houses, may have served as the locus for such shrines.

In later times, Herakles was regarded as a guardian of the house. Above the entrance to the house was placed the inscription "Here the gloriously triumphant Herakles dwells; here let no evil enter."

Rites of Passage

As mentioned above, a newborn child was carried around the hearth in an rite called the amphidromia on its fifth or tenth day of life (which is uncertain). Heidrun Rose suggests that this exposed the child to the “beneficent radiation of Hestia,” and emphasized the connection between the baby and the adults who were to be his kin. On this day, too, those who were involved in any way with the birth performed ritual washing. This was to eradicate the birth pollution.

Robert Parker states that the amphidromia probably served to unite symbolically the newborn with the sacred center of the house, much like the katachysmata, a ritual which served to join brides and newly-bought slaves to their new homes.

The wedding procession, or gamos, began and ended with the hearth and marked the bride’s transition into her new oikos. Vase paintings often show both mothers; the bride’s mother carried torches lit from her home-hearth, which protected her daughter during the procession, while her mother-in-law, who held torches lit from her respective hearth, received the bride into her new husband’s home. Carrying the wedding torches was a significant role for Greek mothers.

After the bride left her mother, and thus, the protection of her household hearth, she joined her new oikos in the rituals of incorporation. The first ritual, the katachysmata, is mentioned in a fragment of the 5th century B.C.E. comedian Theopompos: “Bring the katachysmata; quickly pour them over the groom and the bride!” This ritual took place at the hearth. The katachysmata was also poured over the heads of another category of household inductees, newly-bought slaves. This mixture contained dates, coins, dried fruits, figs, and nuts and was meant to represent good seasons, and thus good auspices for the new member of the household. The groom led his new wife to the sacred hearth of her new oikos, where Hestia waited, sceptre in hand, to unite her with the hearth and thus receive her into the household. This is an artistic representation; Hestia herself had no religious image.

Several rituals associated with death and burial preparations occur in the ancient Greek home. First, when a family member dies, the home is polluted. This pollution requires its own cathartic rituals, which I will discuss below. Second, the washing and laying out of the corpse takes place within the oikos. Third, after the funeral, the oikos must be cleansed of the death pollution, and the sweepings of the home are offered to Hestia in the hearth-fire.

Several tragic characters have prior knowledge of their deaths and carry out some of the necessary rituals beforehand; they bathe in ritual water, array themselves in the proper funereal attire, say a prayer to the goddess of the hearth, Hestia, and bid farewell to their loved ones.

After a member of the oikos died, the surviving members of the household washed the body. Often, women were charged with this task. The prothesis, or the laying out of the body, also occurred within the house. The body was laid on a kline, or couch, and lekythoi, or other small jars of oil, were placed around it.

After the funeral took place, it was necessary to cleanse the house where the death had occurred. For example, an inscription from Keos, dating to the second half of the fifth century B.C.E., states that the house was purified the day after the funeral with seawater and the ceremony terminated with offerings to Hestia at the hearth.91 This final rite, the offering to Hestia, must have concluded an ancient Greek’s “circle of life.” From the first rite of life, the amphidromia, which centered around the hearth, to the last, the final cleansing of one’s soul from the house in which it died, returned back to Hestia.

Miasma (Pollution):

Ancient Greek houses were considered polluted when a death or birth occurred within. In order to avoid these types of pollution, the Greeks created cleansing rituals. Water is the most widespread agent of purification in Greek cathartic rituals. It was required that a person was ritually clean before sacrificing or pouring libations, and by extension, this requirement probably applied to other religious activities. One prescription for purification was to wash one’s hands or bathe. The water for ritual washing often had to be drawn from a specific source, most often a source from outside the house.

Outside of homes where a birth or death had occurred, the household set up a perirranterion, a basin which stood on a pedestal, filled with water. Not only did this basin serve as water for the purification of those entering and leaving the house, but it also served as a token of warning to those who wished to avoid coming into contact with impure, or polluted, households.

While the birth of a child temporarily polluted the ancient Greek household, pregnant women were sometimes the cause of, and also subject to, miasma. During the first forty days of pregnancy, a pregnant woman was not allowed to enter a shrine. However, in the later stages of pregnancy, women were urged to visit the sanctuaries of those deities who oversee childbirth. When outside of her oikos, a pregnant woman was not a source of pollution to others, but instead must be wary of incurring the pollution of others. Pregnant women and those who are about to marry are two classes of people who stand on the cusp of an important transition and are thus susceptible to pollution.

Those who came into the house where a pregnant woman lay were polluted for three days. This birth-pollution could not be passed on and after three days the impure person was cleansed of the miasma. Other purificatory measures were taken in order to eradicate the household of birth-pollution. A baby’s naming ceremony and its amphidromia took place on either the fifth or the tenth day after birth.103 Each of these initiation rites for the newborn was accompanied by rituals and sacrifices. These rites, which probably took place in the courtyard of the house, might have served not only to introduce the child to the oikos, but also to purify anyone involved in the birth, as well as the entire oikos.

The ancient household was polluted when a death occurred within. Similar to childbirth, at this time a basin of water, drawn from a specific source, was placed before the door of the house as a token of warning to those who wished to avoid miasma. It also functioned as water with which visitors could purify themselves after having encountered the pollution within the house.

In order to eliminate the pollution incurred after coming into contact with a polluted household, one needed only wash his or her hands with purifying water. This was similarly true for the house which was polluted by death. After their family member was buried, the family cleansed the house with seawater. This rite served to purify the house of residual miasma.

Ritual Washing

Several domestic rites have a component of ceremonial bathing or hand-washing. During her wedding preparations, the bride’s ritual bath required elaborate ceremony. The loutrophoros, which literally means “one who carries bathwater,” was a vessel used specifically for transporting the water for prenuptial baths from the source prescribed for religious ceremonies. The women of the family joined the bride to parade to the fountainhouse, usually with a young girl carrying the vase. After the procession, the bride would bathe in preparation for her upcoming nuptials. The loutrophoros, which symbolized the ritual prenuptial bath, became synonymous with ancient Greek marriage. For this reason, the vessel shape, either ceramic or stone, came to be used as a grave marker or funerary offering for someone who died before he or she was married.

The death of a family member also necessitated ritual washing. The corpse was given a ritual bath by the women of the oikos. Seawater was the primary cathartic element in funerary rites, and so, it was the type of water used for washing the body. This rite could be compared to the ritual bathing of the bride and groom before their marriage. While the latter bath serves as a ritual in the transition from one stage of life to the next, the bathing of the corpse marked the end of a life, itself a transition.

[1] See KM Swinford, The Semi-Fixed Nature of Greek Domestic Religion, http://etd.ohiolink.edu/view.cgi?acc_num=ucin1155647034

Introduction

This site provides information on ancient pagan household rites and suggestions for designing and following similar rites in the 21st century.

A forum will offer a vehicle for members to discuss problems of integrating ancient forms of piety into modern living, and finding spiritual significance and fulfillment in these paths.

Contributions from members will be welcome if they are on-topic and free of spam, discourtesy and missionizing.

A forum will offer a vehicle for members to discuss problems of integrating ancient forms of piety into modern living, and finding spiritual significance and fulfillment in these paths.

Contributions from members will be welcome if they are on-topic and free of spam, discourtesy and missionizing.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)